Reading on mobile? Watch Patrick Haggerty talk about Lavender Country

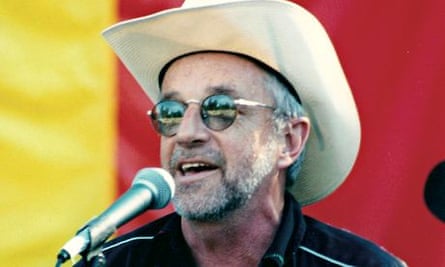

'We were mad," says Patrick Haggerty. "We'd had enough – and music was our best option." Haggerty is talking about the anger he was feeling four decades years ago – anger he channelled into an extraordinary country song that went on to attract a certain amount of notoriety.

As a genre, country can usually be relied on for certain staples, chief among them tears, beers, big hats and patriotic rabble-rousing. It is not a genre you'd expect to produce a gay-rights anthem called Cryin' These Cocksucking Tears, as Haggerty's track was titled. It kicks off with the words: "I'm fighting for when there won't be no straight men." Haggerty, who was the singer and songwriter with the beautifully named Lavender Country, adds: "People call it brave, but a more appropriate adjective for where my head was at back then is 'rabid'."

Released in 1973, Cryin' These Cocksucking Tears is one of 11 astonishing songs on Lavender Country's eponymous and only album. The first in a very short line of out-and-proud country records, the LP has been an obscure curio for most of the intervening four decades, but its recent rerelease has thrown fresh light on the difficult relationship between lesbian and gay people and America's most conservative music genre.

An aspiring country singer raised on a dairy farm not far from Seattle in the northwest of the US, Haggerty was uncompromising right from the start. In the 1960s, he was kicked out of the Peace Corps for being gay. He moved to Seattle in 1970, aged 26, attracted by its reputation as one of the most progressive cities in the US. There he formed Lavender Country with pianist Michael Carr, fiddle-player Eve Morris and "token straight guy" Robert Hammerstrom on Dobro.

The band were active at an organisation called the Counselling Service for Homosexuals, so in return it "passed around the hat", enabling them to buy studio time, press 1,000 copies of their album, and send it out to alternative radio stations and community groups along the Pacific coast. One DJ lost her licence for playing Cryin' These Cocksucking Tears.

Haggerty viewed the record as part of a information drive to explain what it meant to be gay in the early 1970s – and provide reassurance. "It was primarily a record for the lesbian and gay community, especially for people trying to come out," he says. "In the early days of the gay movement, public education was a big deal. I mean, the American Psychological Association still felt gays were mentally sick. All that horseshit. There was so little valid information and the record was good for that. It gave definition to ourselves, rather than accepting the absurd definition handed down by society. "

The surprising thing about Lavender Country is not that its members were so fired up, but that they chose country music as their platform. Haggerty insists it was not an ironic choice, nor deliberately provocative. "I used that music because it was what I knew and loved," he says. The area where Haggerty grew up was a country stronghold. He also points out that country music puts a particular emphasis on words, and he had plenty to get off his chest.

Certainly, the lyrics on Lavender Country are funny, furious, explicit and touching: the album's impetus may have been political, but its content is deeply personal. Georgie Pie is a sad and funny rebuke to a lover lacking the courage of his sexual convictions. "Would your pulses pound if I found / The stains in your underwear?" it asks, while on Waltzing Will Trilogy, Haggerty sings: "A sizzle of electro-shock keeps his fantasies in fascist shape / They call it mental hygiene, but I call it psychic rape." And Come Out Singing moves the focus to the bedroom: "There's milk and honey flowing / When you're blowing Gabriel's horn."

Carr recalls that Haggerty wrote some of the songs following his split from a "cute Jewish doctor who was still in the closet". Gay themes aside, Lavender Country is in many ways a classic country record, with its keening harmonies, rolling piano and cracked heart. Keenly followed by Seattle's vibrant alternative-left community, the band performed regularly at gay-themed events between 1973 and 1975. The peak was an appearance at San Francisco's Gay Pride, playing on a flat-bed truck with Harvey Milk, at the time the most prominent LGBT political figure in America, in attendance.

But by the mid-1970s, the band had fizzled out. Although they had made little impact on straight fans, and far less on country music as a whole, the music and message endured. When the album was previously reissued, in 2000, its historic value was recognised with a place in the Country Music Hall of Fame. Around the same time, Haggerty began working with Doug Stevens, an independent artist from San Francisco who, inspired by Lavender Country, founded the Lesbian and Gay Country Music Association.

Despite establishing important precedents, Haggerty, Stevens and other openly gay country artists such as Sid Spencer and Mark Weigle (whose most famous song is The Two Cowboy Waltz) seemed stuck on the margins. Even kd lang, until recently the sole high-profile artist to challenge country's hetero-orthodoxy, bypassed the Nashville sound and system on her way to stardom.

Which is why Chely Wright coming out as a lesbian in 2010 was so significant. A glossy, mainstream country singer with several hit singles under her belt (not to mention a much-publicised affair with male country star Brad Paisley), Wright is a direct product of Nashville and its Music Row. "The mere fact that someone like me came out is progress," she says. "But that progress is still slow. I get support from progressive country fans, but in equal measure I'm told that it's a deal-breaker for other fans."

Wright believes the notion of Nashville as a deeply conservative town is simplistic. "People in the industry – studios, labels, radio programmers – are generally open and understanding," she says, "but the fanbase is a different thing." Attending a country concert recently, she looked around and decided it would be unwise to hold hands with her wife Lauren. "I wouldn't call the industry homophobic, but they're afraid of the fear lots of fans have about gay people. So they package us as straight, and we let them." Why? "Because we all want to be part of the big game."

Like kd lang, 43-year-old Wright came out publicly having already established a successful career. Declaring her sexuality as an ambitious 19-year-old would, she says, have been "idiotic". Even now, she doubts whether an openly gay country artist could break through from the grassroots. "We're not there yet. I wish we were, but I can't see a new gay artist being taken around radio stations by a credible record label in Nashville." Nor does she believe the mass market is ready for the kind of explicitly gay lyrics heard on Lavender Country.

While Wright is a successful – if divisive – gay country artist, it was Patrick Haggerty who helped open the door, despite never making it through himself. Now 69, and playing songs for people with Alzheimer's in nursing homes, he recognises that Lavender Country scuppered his professional musical ambitions. "There was no way I was going to have a career in Nashville afterwards," he says. "It defined the parameters of how my life would go, especially musically, but I made that choice consciously. I've always been glad I made the album."

Now that it's been boosted by a lavish rerelease on the hip US indie label Paradise of Bachelors, Haggerty hopes the album will, finally, "enter the lexicon of significant American music" and be judged on its artistic merits. When Lavender Country played a one-off show in Los Angeles recently, for the first time ever their audience was not primarily gay. "They listened very closely and really appreciated it," says Haggerty, with something akin to amazement. "It's important that I've lived long enough to see the culture develop to the point where audiences are prepared to accept Lavender Country. Sure, we're still kicking down the closet door in Nashville – but I think we're on the cusp of something."

Lavender Country is out now on Paradise of Bachelors.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion