Modern Americans tend to think of Walt Whitman as the embodiment of democracy and individualism, a literary icon who lifted up the common man when he wrote, “I Hear America Singing” in his revolutionary free-verse poetry collection Leaves of Grass. But have you ever considered Walt Whitman, the brand?

“Walt Whitman believed in this book. He knew that ‘Leaves of Grass’ was unique. It provoked people, and he realized the controversy would sell it.”

Starting in the late 19th century and continuing today, Whitman’s name, image, and writing have been employed to sell a wide range of consumer products, from tobacco and whiskey to fighter planes, life insurance, and wax beans. The range of Whitman-themed marketing is even more surprising when you realize that in 1855, his self-published book, Leaves of Grass, was considered startlingly obscene and repugnant, flying in the face the prevailing buttoned-up Victorian mores of day. But thanks to smart personal brand management on the part of Whitman and his champions, within 30 years, public opinion of the poet made a 180.

When he was an elderly man disabled by stroke and disease in 1890, a handful of cigar manufacturers started to adopt his name and face for their cigar brands—without asking—even though Whitman didn’t even smoke. The iconoclast had also argued in favor of Temperance and Prohibition as a young man because his father was an alcoholic, but more than 100 years later, in 2016, Whitman appears on at least two brands of craft beer.

In “Song of Myself,” Whitman declared, “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.” Which helps explain why Whitman’s image and quotes have been successfully mined to sell everything under the sun, including vices, like tobacco and booze, that he didn’t personally relish. His words fit both patriotic, World War II military-contractor pitches and late 1960s anti-war political art. Because he’s entered the pantheon of Great American Writers, he’s often depicted as a white-bearded, respectable poet for taste-making intellectuals, as fundamentally American as the Founding Fathers. Even as he’s exploited to sell mainstream consumer products, unions and anti-capitalist protesters embrace him as the earthy voice of the common working man, and LGBTQ activists and artists hold him up as a symbol of rebellious homosexual eroticism.

Top: A tin cigar box offering the “Poetic Comfort” of Walt Whitman Cigars, produced by Barnes, Smith & Co. in Binghamton, New York. Above: A can label for Poet Brand apple sauce, sold at the Walt Whitman grocery chain in the 1930s. (Photos courtesy of Ed Centeno)

For the past 28 years, Connecticut ephemera collector Ed Centeno has gathered every piece of Whitman memorabilia he could get his hands on—from commemorative stamps and cancellations to Whitman-branded bubblegum and digital downloads of TV clips mentioning Whitman. Today, Centeno’s collection numbers around 2,000 objects, and he regularly curates Whitman exhibitions. Since the 150th anniversary of Leaves of Grass in 2005, Centeno has been involved in commissioning new Whitman-themed art and petitioning post offices for cancellations and new U.S. stamps honoring the poet.

Centeno started out as a philatelist, as one-time president of the national Gay & Lesbian History on Stamps Club and editor of the club’s “Lambda Philatelic Journal.” In the 1980s, while working on an article about gay and lesbian poets who have been honored on stamps, Centeno discovered that Whitman spent the final years of his life in Camden, New Jersey, the town where Centeno lived as a teenager.

“His house was only a few blocks away from where I lived,” Centeno says. “I had walked by that house many times and didn’t realize that somebody as famous and prominent as Whitman had lived there. That’s how my fascination started, and I began to study his poetry. As a gay man, I can relate to his emotions and struggles. I love the fact that he was an entrepreneur who believed in his work, which still resonates in the 21st century. How many 19th-century poets can you say that about?”

Before Walt Whitman’s final home in Camden, New Jersey, opened for tours, you could buy photo postcards of the site, like this one postmarked 1906. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

Born into an impoverished Long Island family in 1819, Whitman began working for printers around the New York City area as a teenager. As he became an adult, he took jobs as a typesetter and a teacher. He wrote poetry and prose for newspapers, and eventually started his own, “The Long Islander,” when he was just 19 years old in 1838—and he sold the paper after running it for 10 months. In 1842, he published a successful pro-Temperance novel, Franklin Evans; or The Inebriate, which he later called “a damned rot.”

“A lady from Pasadena wrote him in the 1880s to ask if she could produce a calendar using quotes from his poems. Whitman said no. He said that his poems are not to be cut and pasted.”

Eventually, Whitman came across an 1844 Ralph Waldo Emerson essay, “The Poet,” which calls for a distinctly American poet to write about the country’s noble ideals and achievements, as well as its transgressions. At that point, scholars and students in the United States, which was not even 70 years old, only read poetry from the United Kingdom and other European countries. Whitman began to undertake this project in 1850, with the desire to create an epic that rejected the standards of rhyme and meter, using a cadence similar to that of the Bible. (He was not the first English-language poet to write in “free verse,” but he became the most famous, which is why he’s known as “The Father of Free Verse.”)

In June 1855, Whitman paid a print shop to let him typeset and print 795 copies of his poetry collection Leaves of Grass—in the end, only 210 were bound with the trademark green cloth cover. This first edition, only 95 pages, has no byline, just an engraved portrait of 35-year-old Whitman as a “rough” in working clothes on the frontispiece. At line 500, the poet calls himself “Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos, disorderly, fleshly, and sensual, no sentimentalist, no stander above men or women or apart from them, no more modest than immodest.” It’s part of the first 1,336 line poem, constituting more than half the book, that later came to be called “Song of Myself.” The book included just 11 other poems.

Only 210 copies of 1855’s Leaves of Grass were bound with this front cover, and only 179 are known to exist today. (From the Drew University Library in Madison, New Jersey)

“You have to remember that this book was awkward-looking, a long, thin book,” Centeno says. “It was free verse, which was almost unheard of. It was not romantic. It didn’t have rhyme. Most of the poems didn’t even have punctuation, and the title page didn’t have the name of the poet. The first poem went on and on for pages, randomly talking about anything, from the street scenes and the common people to death and the self. He only sold three copies of it at first, one of them to the Philadelphia Library. Only 210 copies were bound because back then, most books were sold unbound, and then the buyer brought them to a binder.”

“As a gay man, I can relate to Whitman’s emotions and struggles. His work still resonates in the 21st century. How many 19th century poets can you say that about?”

Not discouraged, Whitman sent a copy to his inspiration, Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of the most esteemed and revolutionary thinkers, lecturers, and writers of the day, who promoted the radical idea that God lives in everyone and everything. Emerson responded to Whitman with a gushing letter about the book, saying: “I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom America has yet contributed.” Whitman knew this endorsement would raise his profile as a writer, so he set about marketing himself: He gave the letter to Charles Dana to publish in the “New York Tribune.” This sparked the interest of critics like Rufus W. Griswold, who reviewed Leaves of Grass, writing, “It is impossible to imagine how any man’s fancy could have conceived such a mass of stupid filth, unless he were possessed of the soul of a sentimental donkey that had died of disappointed love.”

Still, Emerson’s encouragement inspired Whitman to republish Leaves of Grass in 1856, through Brooklyn publisher Fowler and Wells, with an additional 289 pages, including 20 new poems and Emerson’s letter in the appendix. Whitman then put a quote from the letter on the spine in gold leaf: “I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career.” Whitman didn’t bother to ask Emerson if he could use this private message for public marketing, so his behavior didn’t set well with Emerson. And those accolades only brought out Whitman’s harshest critics, who called his work sinful garbage that should have been burned rather than printed. It was, after all, published during the height of American prudishness. This edition sold worse than the first.

The frontispieces for both the 1855 and 1856 editions of Leaves of Grass feature a steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer—from a lost daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison—showing a 35-year-old Whitman in laborer’s clothing. (From the Drew University Library in Madison, New Jersey)

“Leaves of Grass was considered obscene and very offensive,” Centeno says. “Remember, this was 1856, early in the Victorian Era. Writing about the ‘body electric,’ touching your own body, or swimming nude in the river was absolutely unheard of. It was a very daring work to publish. Some of the reviews in credible publications called Whitman a hog or a lunatic. Somebody said he should be locked away and never to be given a pen, not even to write his name on paper.

“What I love about Whitman is that he was an entrepreneur,” Centeno continues. “He believed in this book and his craft. He knew that Leaves of Grass was unique. He knew that it was something that provoked people, and he realized the controversy would sell it.”

Emerson’s protégé, Henry David Thoreau—who published his meditation on living in nature, Walden; or Life in the Woods, in 1854—was quite taken by the democratic nature of Leaves of Grass, which he first read in 1855, though he was also troubled by the sensual aspects of the poems. When poet Bronson Alcott took Thoreau to meet Whitman in 1856, they got along, even though Whitman’s joie de vivre clashed with Thoreau’s “morbidity.”

The frontispiece and title page for the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass presented a more refined image. (From the Z. Smith Reynolds Library, Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina)

Whitman, not making money off his poems, had to return to journalism, taking a job at Brooklyn’s “Daily Times,” where he worked until 1859. A recent academic discovery revealed that during that time, Whitman produced a series of columns, 47,000 words total, on healthy living called “Manly Health and Training” for the “New York Atlas” under the pen name Mose Velsor. In these essays, Whitman espouses his opinions on sex, diet, bathing, sports, depression, shaving, and shoes and warns against “too much brain action and fretting.”

Meanwhile, the outrage over his last edition of Leaves only prompted Whitman to write 124 more poems, which he began to group in “clusters” for the next edition of Leaves of Grass. This edition was first published by Thayer and Eldridge in Boston in 1860. One cluster became known as the “Calamus” poems, which are now considered homoerotic in nature, revealing Whitman’s sexual desire for men, possibly a lover named Fred Vaughan.

This edition featured a frontispiece engraving of a serious, gray-haired 40ish Whitman wearing an elegant cravat and a title page with lovely, scrolling lettering. This time, the book received positive reviews in Europe, where critics asserted he’d tapped into the wild, primitive pulse of the young country known as America, although many American critics were still disgusted by it.

A first-day cover commemorates the first American postage stamp honoring Walt Whitman in 1940. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

“That edition did very well, selling between 2,000 and 3,000 copies,” Centeno says. “He received quite a lot of attention for that publication, not because of the ‘Calamus’ poems as the word ‘homosexual’ hadn’t even been coined. In those days, it was common for men to be very affectionate toward each other. He was criticized for what are called his ‘straight poems’ like ‘I Sing the Body Electric’ and ‘A Woman Waits for Me.’” The meaning of the latter poem is still hotly debated, particularly as to whether he’s talking about consensual passion or rape when he declares himself “undissuadable” in his quest to impregnate the waiting lover.

“It is impossible to imagine how any man’s fancy could have conceived such a mass of stupid filth, unless he were possessed of the soul of a sentimental donkey that had died of disappointed love.”

Whitman absolved himself of some of his reputation for vulgarity—at least in the North—when “Harpers Weekly” published his patriotic poem “Beat! Beat! Drums!” in its September 28, 1861, issue, more than five months into the American Civil War. Whitman’s brother, George, had joined the Union Army and was sending him colorful letters from the battlefront, which inspired Whitman to move to D.C., where he worked as a clerk and volunteered as a nurse tending to soldiers dying of disease and battle wounds at the Army hospitals. He documented this heart-wrenching experience in his essay, “The Great Army of the Sick,” published in “The New York Times” on February 26, 1863.

Thanks to his friend, “Saturday Evening Post” editor William Douglas O’Connor, Whitman landed a clerk job at the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs in January 1865. Shortly thereafter, at age 45, Whitman met 21-year-old streetcar conductor Peter Doyle, with whom, it’s believed, he developed an eight-year romance. Around that time, Whitman’s health was starting to deteriorate, because he’d been exposed to so many communicable diseases like malaria and typhoid fever when he was taking care of sick soldiers.

This 1924 calendar features a different Whitman quote on each page—a concept Whitman rejected in the 1880s. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

“Whitman would go to the bed of one of those poor men who were dying,” Centeno says. “He would write a letter for him, or bring him candy or tobacco out of his own money. The next day, he would find that the bed was cleaned up and the soldier was gone.”

“In 1855, writing about the ‘body electric,’ touching your own body, or swimming nude in the river was absolutely unheard of.

“In the final months of the war, Whitman, a staunch abolitionist, prepared to publish 500 copies of Drum-Taps, a book of pro-Unionist poetry that depicted the war as a horrible necessity to restore America to its highest ideals. On April 9, Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union general Ulysses S. Grant. Five days later, Peter Doyle attended the same play at the Ford Theater as Abraham Lincoln, where the president was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. Hearing his companion’s story, Whitman quickly wrote a poem about the April 19 burial of his beloved president, “Hush’d be the Camps To-day,” and inserted it into Drum-Taps, which contained 53 poems when published in May.

Despite his growing reputation as a patriot, Whitman came under fire when Secretary of the Interior James Harlan, newly appointed by President Andrew Johnson in June, was on a quest to purge his office of lazy employees. Harlan found Whitman revising Leaves of Grass at his desk—not only was he blowing off his job, but he was also producing text Harlan found morally objectionable—so Harlan fired him on the spot. O’Connor, a devotee of Leaves, was outraged and petitioned to get Whitman another government job, this time with the Attorney General’s office, where Whitman interviewed former Confederates seeking presidential pardons.

The Walt Whitman Bridge, which opened May 16, 1957, crosses the Delaware River to connect Camden, New Jersey, to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

Mourning Lincoln that spring, Whitman wrote two more poems about his death, “When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d” and “O Captain! My Captain!”, which he had published in October 1865 in an 18-page supplement to Drum-Taps entitled Sequel to Drum-Taps. On November 4, 1865, “New-York Saturday Press” published “O Captain! My Captain!”, and because it follows a more traditional rhyme and meter than the original Leaves of Grass pieces, it was a tremendously popular poem with a public still reeling from the murder of the celebrated leader. Whitman felt chagrined that his most successful poem followed such a standard format, so he wasn’t pleased that it was frequently republished in anthologies and taught in schools the rest of his life.

O’Connor, incensed about Harlan firing Whitman from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, put out a doting biographical pamphlet on Whitman titled The Good Gray Poet: A Vindication in January 1866, which was designed to reform and soften Whitman’s image for the American middle class. This biography did help sway public opinion, as readers began to embrace the 46-year-old poet as a sage, gray-haired champion of American values.

Starting the 1930s, New Jersey shoppers could buy Walt Whitman coffee at Walt Whitman stores, run by the Camden Grocers Exchange. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

Capitalizing on his revamped image, Whitman published the fourth edition of Leaves of Grass in 1867, with rewrites to shift the focus from the individual to the “collective self” and to urge blacks and whites, Unionists and ex-Confederates to come together as one nation. Published in New York, the 1867 edition had multiple issues, two of which absorbed his previous Civil War poetry books, and one of which included a new cluster of Civil War poetry called “Songs Before Parting.” It was in the 1867 edition Whitman first published his famous tribute to the American artisan, “I Hear America Singing,” a revision of poem No. 20 from his 1860 Leaves of Grass.

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear,

Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe

and strong,

The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam,

The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off

work,

The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deck-

hand singing on the steamboat deck,

The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing

as he stands,

The woodcutter’s song, the ploughboy’s on his way in the morn-

ing, or at noon intermission or at sundown,

The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work,

or of the girl sewing or washing,

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else,

The day what belongs to the day—at night the party of young

fellows, robust, friendly,

Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.

Across the pond in England, writer and critic William Michael Rossetti published an article praising Whitman in the “London Chronicle” in 1867, and his glowing review was reprinted in several publications in the United States. The following year, Rossetti—a leader in a British back-to-nature arts movement—was asked by a U.K. publisher to edit a collection of Whitman’s writing.

This 1939 World’s Fair sculpture of Walt Whitman, “The Open Road,” took its name from the verse: “Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road, / Healthy, free, the world before me, / The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.” (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

For Poems by Walt Whitman, Rossetti didn’t alter Whitman’s poems; he simply removed the ones that would be most offensive to British censors, tweaked Whitman’s preface, and then added a note about his objections to the phrasing and particular poem topics.Even though Whitman wasn’t happy with “the horrible dismemberment of my book,” as he called it, Rossetti trumpeted the writer as one of the greatest living poets, which helped bolster Whitman’s popularity in both the United Kingdom and the United States. Whitman became an icon to young, gay British writers, including Oscar Wilde and Edward Carpenter, as well as Bram Stoker, who would publish Dracula in 1897.

Whitman’s fifth edition of Leaves of Grass (1871-’72) included a pamphlet of 74 poems entitled “A Passage to India,” celebrating the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal, which he believed would not only connect the East and West through commerce, but also through spiritual, cultural, and romantic bonds. This publication went largely ignored by critics, although the reviewers who did acknowledge it commented on Whitman’s sense of democracy and universality.

In 1873, Whitman, at 53 years old, suffered a stroke, which rendered him partially paralyzed, and he moved in with his brother George, who had a home in Camden, New Jersey, just across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. Three years later, Whitman put out another, largely unchanged version of Leaves of Grass. Starting in April 1879, Whitman gave annual lectures honoring Lincoln’s death. In these lectures, he described the dramatic scene at the Ford Theater, drawing on Peter Doyle’s eyewitness account, and portraying the president’s assassination as a holy sacrifice that brought the broken country back together.

A menu from Hotel Walt Whitman, which became a regular meeting spot for the veterans organization American Legion in the late 1920s and early ’30s. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

What is now considered the definitive edition of Leaves of Grass, the seventh, was first printed in late 1881. “Mark Twain’s publisher, James R. Osgood and Company, was interested in publishing the seventh edition,” Centeno says. “Whitman went to Boston to supervise the printing himself. While he was there, he met with Emerson, who told him that he should tone down some of those poems because they were a little too racy, especially, ‘I Sing the Body Electric,’ ‘To a Common Prostitute,’ and ‘A Woman Waits for Me.’ Whitman said ‘No, I’m going to publish it the way I want,’ so the publisher let him.”

“Did these companies ask Walt Whitman if they could use his name and image? Did he receive any money for it? No and no.”

The book sold 1,500 copies after it was released in October before a Boston district attorney threatened to sue the publisher, thanks to the national Comstock Law that Congress passed to ban the trade and circulation of material considered “obscene.” “The Boston district attorney said, ‘Unless it gets cleaned up or edited, you are not allowed to print the book here anymore,’” Centeno says. “The publisher asked Whitman if he could clean up or delete some of the poems. When Whitman said no, then the publisher gave all the plates to him, which he brought to Philadelphia, where other publishers resumed printing the book the following spring. Of course, that controversy raised a lot of publicity.” In the end, this edition sold more than 6,000 copies, earning Whitman $1,000 in royalties.

In 1884, Whitman, then 64, bought the house on Mickle Street in Camden that Centeno walked by so frequently. The ailing Whitman was bed-ridden there for the final years of his life. At that point, the United States had changed drastically since Whitman first published Leaves of Grass. In the aftermath of the Civil War, American industry exploded in a period Mark Twain sarcastically dubbed “The Gilded Age,” from 1870 to 1900. The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 allowed entrepreneurs, with the help of displaced soldiers and immigrants, to build the West. More and more rural folk moved from their tight-knit communities to cities, which were also flooded with immigrants from around the globe, working in factories that churned out the latest gadgets and products.

In this 1963 magazine ad for Old Crow bourbon, Walt Whitman is portrayed as an elegant elderly writer who’s wealthy enough to have a maid. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

In these urban centers, Americans had more access to literature, other cultures, and news about scientific discoveries. They started to reconsider long-held religious beliefs and sexual mores, even as social conservatives attempted to tighten their grip through shaming editorials and legislation like the Comstock anti-obscenity law. When Leaves of Grass was reissued again in 1889 and 1891, it was no longer as shocking to readers. Instead, the elderly Whitman, with his big white Santa beard, became the picture of the wise poet of American democracy, progress, and individualism. Complete strangers started to mail him asking for his autograph.

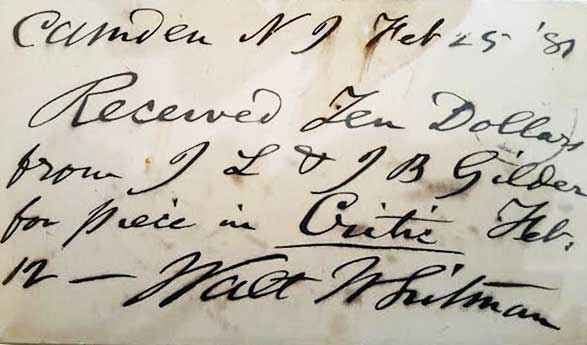

“By the 1880s, Whitman was getting a lot of requests to use his name,” Centeno says. “For example, a lady from Pasadena wrote him in the 1880s to ask if she could produce a calendar using quotes from his poems. Whitman said no. He said that his poems are not to be cut and pasted. We don’t know if the calendar was ever produced. A public school in Maine wanted to adopt his name during the 1880s, and universities were starting to ask him to commission original poems to be read in ceremonies.”

During the Gilded Age, new industrial technology, particularly in chromolithography and tin-stamping, caused an explosion in product branding and advertising with colorful product labels, tin boxes, and tin signs. This new era of marketing meant familiar literary characters and beloved authors could be used to drum up excitement for unknown products.

This envelope advertising Ostrom, Barnes and Co.’s Walt Whitman Cigar is probably similar to the one first shown to Whitman in 1890. The poet didn’t smoke, and the cigar makers never asked him if they could use his name. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

So when cigar maker Frank Hartmann bought the Spark Cigar Factory in Camden, New Jersey, in the late 1880s, the celebrated local bard was an obvious mascot. By 1890, his company introduced its Walt Whitman brand of cigars. But Hartmann wasn’t the only entrepreneur to have this idea: At least a few companies in the cigar manufacturing center of Binghamton, New York, started offering their own Walt Whitman cigars around the same time. The branding arrived as Whitman was facing his mortality and doubting whether Americans were truly touched by his life’s work. When Whitman disciple Horace Traubel presented the poet with an 1890 envelope advertising Walt Whitman cigars, he reported that Whitman exclaimed, “That is fame! … It is not so bad—not as bad as it might be: give the hat a little more height and it would not be such an offense.” In 1892, when he was 72, Whitman died of complications from his illnesses.

“Did they ask him if they could use his name and image? Did he receive any money for it? No and no,” Centeno says. “At that time, trademark laws were looser. Tobacco was one of the largest industries in the United States, and nearly everybody smoked. The cigar packaging employed a variety of enticing images, including famous people. At the time, Whitman was celebrated for his writing, his Lincoln lectures, and his Civil War volunteerism, so the cigar companies thought his image conveyed a patriotic, older, respectable writer who might sit down and smoke a cigar. Ironically, he never smoked. But you can sell the public any idea you want.”

This cigar box for the Walt Whitman Cigars made by Brown & Corbin promotes reading and writing as leisure activities. The image is similar to one created by Frank Hartmann’s cigar company, which also sold Walt Whitman Cigars. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

Even as they benefitted from the poet’s leisurely, voluptuary image, the Walt Whitman cigar brands also nudged their consumers to actually read his book. In 1898, Hartmann’s company designed an image called “Walt Whitman Cigars: Blades O’ Grass” showing the writer in front of books stacked on a desk. Not only did they want their customers to smoke, they wanted them to consume Leaves of Grass while doing so.

In 1922, thirty years past the poet’s death, the city of Camden—then home to Campbell’s Soup and RCA Victor—voted to purchase the humble Mickle Street row house where Whitman had died. During the same decade, the Jazz Age, local businesses in Camden began to capitalize on the city’s most famous literary resident, Walt Whitman, the white-bearded poet of American freedom. Flower shops, movie theaters, heating companies, and pharmacies adopted his name. The eight-story Hotel Walt Whitman, replete with 200 guest rooms, a ballroom, and banquet halls, opened in 1925. Inside, the lobby walls were adorned with murals inspired by Whitman’s poems. Naturally, Whitman’s house and the hotel offered tourist postcards, and the hotel, which closed in 1985, produced a wealth of memorabilia for collectors like Centeno: Matchbooks, brochures, menus, receipts, and the like.

Chili sauce was another food product you could buy labeled with the Walt Whitman Brand in the 1930s. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

Starting in the 1930s, Camden Grocers Exchange began to produce Walt Whitman Brand products—like coffee, fruit cocktail, yellow cling peaches, and chili sauce—as well as Poet Brand canned goods such as cut waxed beans, tomatoes, and apple sauce. The company opened at least 44 groceries called Walt Whitman Stores around New Jersey and held beauty pageants for female clerks to compete for the title of “Miss Walt Whitman” to represent the brand at a national convention.

According the Library of Congress,Whitman was so esteemed at this point in American history, that copies of Leaves were given to laborers during the Depression and servicemen during World War II. A sculpture of Whitman named after his poem, “Song of the Open Road,” was installed at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. The United States Postal Service first honored Whitman with a 5-cent stamp in its 1940 “Famous Americans” series, which also included Emerson and novelist Louisa May Alcott (who is also the daughter of poet and early Whitman-enthusiast Bronson Alcott).

Centeno has about 100 envelopes bearing Walt Whitman stamps that were mailed to U.S. servicemen and family members during World War II, which are rare because the envelopes were typically discarded. During that period, Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation produced postcards with sometime-truncated versions of patriotic Whitman quotes like “O America, because you build for mankind, I build for you!” The bottom of these cards read, “Airplanes for our Airmen! That’s Grumman’s Goal!” Centeno guesses that these were probably sent out with promotional materials to clients. Whitman, who frowned on having his poems excerpted, would probably not be happy with this new advertising practice, despite the company’s lofty ambitions.

During World War II, Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation used Walt Whitman quotes to promote its fighter planes. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

In 1953, construction began on the Walt Whitman Bridge over the Delaware River, which would connect Philadelphia to Camden via Interstate Highway 76. The still-functioning Walt Whitman shopping mall opened in 1962 in Huntington Station, New York, thanks to its proximity to the poet’s Long Island birthplace. As the 20th century progressed, other buildings, theaters, plazas, camps, parks, truck stops, corporate centers, schools, AIDS clinics, and think tanks claimed his name.

In the mid-20th century, rebellious Beat Generation poets rediscovered Whitman’s poetry—Allen Ginsberg invoked Whitman’s “barbaric yawp” 100 years after Leaves of Grass with his 1955 poem “Howl,” which openly celebrated gay sex. As Whitman became, once again, the darling of the anti-capitalist counterculture, the “mad men” of New York City’s advertising powerhouses also saw the poet’s potential for shilling products to the whole of mainstream America, not just the regions surrounding Camden or Long Island. Companies like John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance, Rand McNally, Container Corporation of America, and Old Crow Whiskey created ads quoting Whitman or depicting him as an authoritative gentleman poet who endorsed their products.

This novelty gum, named after a Walt Whitman quote, “You are so much sunshine to the square inch,” first came out in 2011, even though its packaging resembles 1960s art. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

During the 1960s, a nun named Sister Cortia Kent threw herself into civil rights and Vietnam War protests making pop-art posters and banners that referenced everything from the Bible to brand logos to the Beatles. For a 1969 poster, she grouped a Whitman poem containing the line “Agonies are one of my changes of garments” with news photos from the war.

This 1970 album by Jesse Pearson and Rod McKuen sets the “erotic words” of Walt Whitman to music. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

The emergence of identity-based academic fields in the 1970s—particularly lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer studies—led scholars to reassess Whitman’s life and poetry, questioning previous biographies that depicted Whitman as completely heterosexual. After research shed new light on Whitman’s sexual interest in men, Centeno notes the tone of Whitman memorabilia started to shift from reverential portraits of a venerable American thinker to brazen depictions of a lascivious sexual revolutionary. “In the 1970s, we started to see his image being used to sell more edgy publications with nudity and racy writings,” Centeno says.

Whitman’s influence touched Hollywood, too, which has honored the poet in both high-minded and satirical ways. In the 1989 film “Dead Poet’s Society,” Robin Williams’ unconventional English teacher fires up a group of teenage boys at an uptight boarding school in 1959 using lines from Whitman’s poem “O me! O life!” On a 1995 episode of “The Simpsons,” Homer is outraged that Whitman has such a large memorial in Springfield; later, his brainy daughter Lisa brings Leaves of Grass to family reading night. Leaves of Grass figures prominently in the third season of the grim drug drama “Breaking Bad” in 2010, when a fellow meth chemist gives Walter White (another “W.W.”) a copy of the book.

In 1883, Whitman promoted his woodsy image with a photo, left, featuring a fake butterfly. In the 1990s, Borders Bookstores tweaked the image, right, to promote their cafes.

The publishing and bookselling industry has also long relied on Whitman’s image to convey the seeming opposites of unconventional bohemian values and elite, refined taste. During the 1990s, Borders Bookstores adapted an 1883 photo of Whitman contemplating a butterfly perched on his hand by replacing the insect with a coffee cup to advertise the stores’ espresso bars. The original photo was also a staged publicity shot, created with a cardboard butterfly to promote the poet’s connection to animals and nature.

Outside of the practice of naming things after the poet, the title of his epic work, which conveniently also describes lovely natural greenery, has been appropriated for brands and locations. “There was a Virginia winery, a little perfume bottle, and even a china pattern called ‘Leaves of Grass,’” Centeno says.

Most recently, Whitman was used to sell Levi’s jeans in the company’s 2009 “Go Forth” advertising campaign; once again, the writer was depicted as the vaunted voice of the true American. A brand of fruity bubble gum named after a Whitman quote “You Are So Much Sunshine to the Square Inch” appeared in 2011 in a cheerful ‘60s psychedelic package that recalls the art of Sister Cortia. (“Oh, it tastes awful!” Centeno says.) Today, you can buy Walt Wit Beer from Philadelphia Brewing Company and Old Walt Smoked Wit Beer from Blind Bat Brewery in Long Island.

In a 2010 episode of “The Simpsons,” Lisa Simpson reads from Leaves of Grass to comfort a beached whale. (Courtesy of Ed Centeno)

Even though modern Americans are well aware of the poet’s lusty side, hardly any ads in 125-odd years have riffed on that first Leaves of Grass frontispiece with a handsome, strapping 35-year-old Whitman standing in rugged clothes, hat cocked, peering at the readers with clear, defiant blue eyes. It’s particularly strange when you consider the way modern advertisers focus on the boundless energy and sex appeal of youth.

“Just about every piece of merchandise that I have—and I have more than 2,000 or something in my collection—depicts Whitman as an elderly white-bearded man,” Centeno says. “I think when people read poetry, they picture a literary father figure or a wise grandfather type. Because of his Civil War poetry and Lincoln lectures, he gained an aura of respect, which I guess advertisers thought would resonate better with consumers. A younger, sexier Whitman might not be taken seriously enough.”

Is this Walt Whitman too green to be taken seriously? Marketers have rarely latched onto this 1855 engraving of the 35-year-old writer of Leaves of Grass. (From the Drew University Library in Madison, New Jersey)

Regardless, it’s amazing the poet’s name still carries such weight in pop culture today, when most 19th-century poets are forgotten or relegated to high-school English classes. That’s probably because Walt Whitman—thanks to his all-embracing and forward-thinking rambles—serves as a mirror for how we want to see ourselves, whoever or wherever we are in the present moment.

“Whitman believed in the power of the people,” Centeno says. “When he says, ‘I sing and celebrate myself,’ he’s not actually talking about himself. He’s really giving permission to readers to do whatever they want. A lot of people think, ‘Oh my God, he was so egoistic, talking about himself so much.’ Noooooo! He’s talking about you. When you read Leaves of Grass, you’re reading about yourself, not him. He’s not interested in bragging about what he wanted; he’s interested in what you can achieve if put your mind to it.”

(To learn more about Ed Centeno’s collection, visit the Historical Society of Riverton, New Jersey, to download his 45-page Walt Whitman Virtual Scrapbook. Pick up Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass,” which is available in the 1855 edition, the 1860 edition, and in its final form. To learn more about Walt Whitman, explore The Walt Whitman Archive, edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. For further reading, check out the paper “The Walt Whitman brand: Leaves of Grass and literary promotion, 1855-1892,” by Eric Christopher Conrad at the University of Iowa and the books “Re-Scripting Walt Whitman: An Introduction to His Life and Work,” by Folsom and Price; “Walt Whitman’s Native Representations,” by Folsom; “The Routledge Encyclopedia of Walt Whitman,” by J.R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings; “A Companion to Walt Whitman,” edited by Kummings; and “In Walt We Trust: How a Queer Socialist Poet Can Save America from Itself,” by John Marsh. Learn more about Camden, New Jersey, history at DVRBS.com.)

Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male

Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male

Cool for Sale, From Beatnik Bongos to Hipster Specs

Cool for Sale, From Beatnik Bongos to Hipster Specs Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male

Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male When the Wild Imagination of Dr. Seuss Fueled Big Oil

When the Wild Imagination of Dr. Seuss Fueled Big Oil First Edition BooksThe first edition refers to a book's first printing run. For some blockbust…

First Edition BooksThe first edition refers to a book's first printing run. For some blockbust… Cigar BoxesIt wasn’t until the Revenue Act of 1864 that all cigars were required to be…

Cigar BoxesIt wasn’t until the Revenue Act of 1864 that all cigars were required to be… Poetry BooksWhether your taste tends to William Shakespeare, William Blake, or William …

Poetry BooksWhether your taste tends to William Shakespeare, William Blake, or William … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

What a wonderful inclusive article about a poet I’ve always loved and admired. The detailed scholarship by Centeno is lucid and lively.

A thoroughly entertaining and educational article–well written, well documented, and well illustrated. The author is to be commended on her clarity and detail and very fine writing. Makes me want to learn more!

Fascinating. It’s sad these days that the most interesting, well-researched, and well-written articles are in no-name publications such as this one.