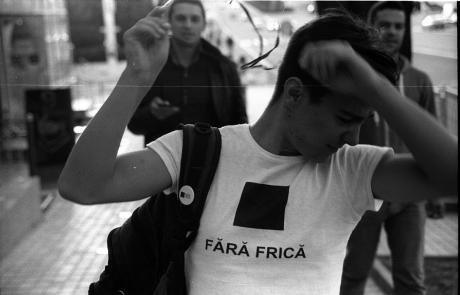

Karolina Dutka, photo from the project "No silence". Published with the permission of the author.In October 2016, photographer Carolina Dutca was preparing for the opening of an exhibition of her work in Tiraspol’s Club 19. But after she posted an announcement about it online, she was asked to visit Transnistria’s security services.

Dutca’s No Silence photo project was the first public declaration that an LGBT community exists in the unrecognised republic, and the authorities were not happy with it. Pressure from law enforcement agencies ensured that the exhibition did not take place.

A year later, the project had been exhibited in Ukraine, Moldova and the Czech Republic, while almost anyone with an internet connection in her own republic knew about her work as well. Since then Carolina has completed several photo projects on subjects that no one in Transnistria is yet prepared to talk about. Now she’s planning to put all her efforts into covering social issues and setting up a creative community that she hopes will help develop civil society in Transnistria.

I met up with Carolina to talk about how art can be the most effective way to start a conversation about sensitive subjects.

Tell me in some more detail about what happened with your LGBT exhibition?

CD: I hid the fact that I was working on a project on LGBT issues until the very last moment, because I knew there might be problems. A day before the KGB contacted me I posted an announcement about the exhibition on “Typical Transnistria”, our most popular VKontakte social media group. Overnight, about 700 comments appeared, with hate speech going viral. I started getting anonymous threats, and someone rang my doorbell and ran away. Then I got called in by the KGB. They told me that there were no LGBT people in Transnistria and that my photos were fakes, so I had to cancel the show. They also said that if I refused, they couldn’t answer for anything that might happen to me. And they threatened that my parents might have problems at work.

What triggered the idea for the project?

CD: About three years ago I got to know a young man who turned out to be gay. He told me about the discrimination he faced, and this was an eye-opener for me — I had never thought about LGBT issues in Transnistria before.

The thing is that the issue is swept completely under the carpet. There is just nowhere where LGBT people can get together. There’s one social media group, “Rainbow Transnistria”, and that’s it. LGBT issues are totally off people’s radar, so my project was the first ever mention of the subject in the public sphere. Because it’s never mentioned, a lot of people think there are just no LGBT people here. Naturally, there have been no opinion polls on the subject. In Chișinău, there is, on the other hand, an organisation called Genderdoc-M, which runs Pride rallies and workshops and carries out research into LGBT issues. But not everyone in Transnistria can go there, for reasons of distance as well as other obstacles.

With no information around, many believe that there are simply no LGBT people here

In Chișinău you can at least go to a Pride rally or hold hands with someone on the street, and nothing will happen to you. People may look askance, but you won’t be in danger. Whereas, I can’t even imagine that happening in Tiraspol.

Many people I know thought I was crazy for raising the subject at all; they believed I was just trying to shock. But I think that we need to talk about the issue. Through VKontakte, I wrote to everyone who subscribed to Rainbow Transnistria, but out of 150 people, only 16 were prepared to participate in the project. Now, post factum, I’ve met lots of people whom I had asked to take part and they have told me that they really wanted to help but were too scared. Many weren’t even ready to meet me, because five or so years ago thugs used social media to set up meetings with LGBT people and then beat them up.

How did the exhibition story end?

CD: I decided to abandon the idea. Club 19, the space where it was due to take place, was ready to organise it regardless and even suggested taking it over, as though it had been their own initiative. But the bottom line for me was the safety of my parents. I know what leverage the local special services can use against people. If I lived on my own I would definitely have gone ahead with it.

Karolina Dutka, photo from the project "No silence". Published with the permission of the author.I did, however, exhibit the project several times in Odesa, Chișinău and Prague. When I was taking my photos across Transnistria’s border with Ukraine, I was really worried that I would have problems during the security checks, but everything went smoothly. No Silence hung in the US Embassy’s Resource Centre in Chișinău all during Pride Month and was visited by around 1,000 people. The centre’s staff were slightly worried about having an exhibition on such a controversial subject on their hands, but I don’t like raising such issues just for a narrow circle of “people like us” — that has no effect at all. My main targets are the people who would naturally avoid such subjects like the plague.

Thanks to all the fuss around the exhibition, a lot more people learned about the subject than if it had taken place

I think that the ban on the exhibition meant that a lot of those people became engaged with the issue. Club 19 is the only free space in Tiraspol, and I can imagine that if it had gone ahead, it would have been mostly visited by people who knew me and were well acquainted with LGBT matters. But thanks to all the fuss, a lot more people learned about the subject than if the exhibition had taken place.

After the exhibition ban, did you find any other people in Transnistria who were prepared to take part in a dialogue on sensitive social issues?

CD: No, for the moment I’m the only documentary photographer involved in studying and working with social issues here. There are other documentary photographers around, but they have a different focus and way of working. They are interested in more everyday subjects: they shoot stories about all the stuff that comes into your head when you think about Moldova and Transnistria — villages, children, nature and so on. And then there is Ramin Mazur, who creates photo projects about Moldovan prisoners serving life sentences. He was born in Transnistria, in Rybnitsa, but works mostly in Moldova.

Weren’t you afraid to get involved in sensitive issues after you’d been questioned by the KGB?

CD: I did think there might be problems from the authorities, but I was probably already prepared for that. I think that if I’d been hauled in again, my previous experience with them would have given me the confidence to have a different kind of conversation. Immediately after No Silence, I started on a project called The Places of Violence, about domestic violence against women, but the KGB showed no further interest in me. Women’s rights are not a taboo subject in Transnistria, but they are still a very sensitive one. While in Russia, domestic violence has just recently been decriminalised, here it was never criminalised in the first place, so there is no legislation on it at all.

Karolina Dutka, photo from the project "No silence". Published with the permission of the author.The problem with the LGBT thing was that there were no statistics on the subject, so I couldn’t argue with the KGB about whether there were such people in Transnistria. Domestic violence is a different matter, as we do have figures for it. Last year, for example, a woman was murdered by her live-in partner in a fit of jealousy and became a statistic on the Department of Internal Affairs database, so the KGB couldn’t deny the existence of the issue even if they wanted to.

One of my aims in The Places of Violence was to talk about organisations that support women who have experienced domestic violence, so that people would know where to turn if they needed help. We have organisations like this, but they are very few and almost invisible. We have, for example, only one women’s shelter in the whole of Transnistria, in Bender.

Why did you decide to get involved with this particular issue?

CD: It was because I had experienced domestic violence myself. Only once — I walked out immediately, so it wasn’t a long lasting thing, but it did happen to me. I think it’s important to show women who have faced this issue that there is no shame in it, at the very least.

In general, if an issue doesn’t touch me closely, I won’t be able to get other people involved in it because I haven’t had that personal experience. I always start from my own experience or the experience of people close to me and then look for others who have been through the same thing and use their help to get my head round the subject.

I was more pleased with the results of The Places of Violence than with any previous project. I had problems finding people to take part in it, and had to pester organisations that support women with violent partners and trawl social media in search of stories. In the end I found 10 women who had experienced long term violence and cruelty. The project was also hard for me psychologically, because I can’t listen to a survivor of domestic violence and then just walk away: I can’t be dispassionate about it.

Karolina Dutka, photo from the project "No silence". Published with the permission of the author.Because this was a multimedia project, I had to absorb the hours-long tapes of our conversations that by the end I felt I knew by heart. I know that my task is to bring these stories to public attention, but when I’m actually with a specific woman and she is telling me how her husband beat her senseless and then poured cold water over her and beat her some more, I want to help her as an individual but I realise that I can’t do that. After this, I feel I need psychological help myself.

But I was so happy to see so many people, and so many of them men, at all three exhibitions and discussions that we ran alongside the project in various towns and cities in Transnistria. Most of the men took part in the discussions and argued with me about the importance of the project, which I didn’t find easy. But what I wanted to do with this project was to plant some thoughts in people’s heads, so that they would start thinking about the issue for themselves.

The censorship and general political situation in Transnistria evidently means that art is the only means people have of expressing their civic consciousness. Has this always been the case or is it something recent?

CD: It’s just a recent thing, and I think that this interest in art and documentary photography arose about five years ago, when the first independent spaces where anyone could organise an event began to appear.

It all started with Club 19 in Tiraspol, where my LGBT exhibition was supposed to take place, but now there are similar clubs in Rybnitsa and Dubăsari. And their independent stance means that they face the same kind of harassment from the KGB. The woman who ran Club 19, for example, was recently forced to emigrate after unknown assailants beat up her son and took care to mention his parents as they did so.

But at least these spaces provide interesting events that stimulate other people to put their ideas into practice. So something is happening: a lot of people have told me, for example, that my projects have inspired them to try something out.

I am always ready to help aspiring photographers and other creative people, because I believe that the appearance of a creative environment that challenges people to ask questions about social issues is a crucial element in the development of civil society.

In Transnistria, political and social questions are usually debated in round table discussions among members of different organisations, but I’m not sure whether this is a useful means of reaching the wider public. We need to talk to people using accessible language and an attractive format, and I feel that photography and art are very powerful tools for changing society and try to use them for that purpose. There are innumerable beautiful photographs in the world — you can go on Google and admire them — but photography for its own sake doesn’t interest me.

Many people of your age dream of leaving Transnistria. Have you thought about doing that?

CD: I used to. Things aren’t easy here and I would have so many more opportunities abroad. But emigration is a difficult subject now. I just can’t see anyone around me who would be prepared to shake the people here up, and they certainly need shaking. We have very fertile ground for development here: everything is just at an embryonic stage. I also know the area: I find it easy and interesting to study — you could say I’ve lived through everything that goes on here. Every now and then I go away for a short time, to recharge my batteries, but I always come back with renewed energy and new ideas.

Translated by Liz Barnes.

The article was drawn up as a part of the "Conflict transformation in the post-Soviet space" research project. The project was supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Germany and carried out by the Center for Independent Social Research (CISR e.V. Berlin)

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.