In early July 1969, a US soldier stationed in Long Bình, Vietnam, opened his army newspaper and came across an article that would change his life. Among the stories of the ongoing war, specialist Henry Baird noticed an unusual headline. Over the past week in New York City, hundreds of homosexuals had fought police in a week-long riot in Greenwich Village, following a botched police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a mafia-run bar frequented by LGBTQ+ people. Years later, Baird would recount to a radio producer that his “heart was filled with joy. I thought about what I had read frequently, but I had no one to discuss it with. And secretly within myself I decided that when I came back stateside, if I should survive to come back stateside, I would come out as a gay person.”

Baird’s story is echoed in the accounts of thousands of LGBTQ+ people across the the world. After Stonewall, things could never go back to how they were before. While the Stonewall riots were a spontaneous eruption of anger against police harassment, they had been a long time in the making, and while the riots lasted only a few days, their repercussions continue to this day. Following this explosion of rage, LGBTQ+ people in New York and further afield transformed the small pre-existing gay rights movement. Soon they were advocating nothing less than “gay liberation”.

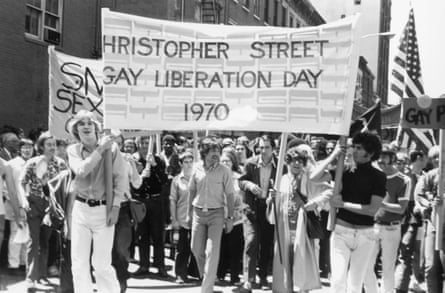

From consciousness-raising groups to fundraising dances, protests outside hostile newspapers to refuges for homeless trans and queer people, this surge in LGBTQ+ organising took many forms, and as the first anniversary of the riots came into view, some in the community began discussing how best to mark what was becoming regarded as the “Bastille day” of gay rights. On 28 June 1970, exactly a year to the day since the police raid, the first Christopher Street Liberation Day was held, attracting a few thousand LGBTQ+ activists. (Christopher Street was the location of the Stonewall Inn, and epicentre of the riots.) Similar small events were held in Chicago, Los Angeles and San Francisco. As the gay rights movement grew, so did the marches, which came to be collectively known as Gay Pride and then Pride parades. Last year, on the 50th anniversary of the riots, more than 5 million people took part in New York’s annual Pride events.

The five decades of struggle that have followed the riots have sometimes lent the impression that the arc of the moral universe does indeed bend towards justice. Within a single lifetime, homosexuality has moved from being a crime and a psychiatric disorder, punished in the US by imprisonment, chemical castration, social ostracisation and a lifetime as a registered sex offender, to a socially and legally recognised sexual identity. Yet Pride marches, and the legacy of Stonewall, remain contentious even within the LGBTQ+ community.

For all its talk of unity, Pride can still divide. To religious and cultural conservatives, Pride parades are nothing less than the public flaunting of deviancy, while many LGBTQ+ people regard today’s corporate-sponsored parades as having sold out the radical, revolutionary demands of the gay liberation movement. Those who were key to the kickstarting of gay liberation – trans people, people of colour and working-class LGBTQ+ people – have gained the least from the mainstreaming of the struggle. For decades a debate has raged between different elements of the community: is Pride supposed to be a protest, or a party?

The roots of that debate go back to its earliest days, and suggest that Pride and the Stonewall riots have always been part of a contentious battle for identity and ownership – a battle that has helped produce the very idea of what being a lesbian, gay, bisexual , transgender or queer person might mean.

The Stonewall riots were not the birth of the gay rights movement. They weren’t even the first time LGBTQ+ people had fought back against police harassment. In 1966, in the Tenderloin neighbourhood of San Francisco, transgender customers of Compton’s Cafeteria had attacked police, following years of harassment and discrimination by both cops and management. Seven years before that, when police had raided Coopers, a donut shop in the city nestled between two gay bars, LGBTQ+ patrons had attacked officers after the arrest of a number of drag queens, sex workers and gay men.

There had been a gay rights movement in the US among people describing themselves as “homophiles” since the late 40s. It wasn’t the first such movement in the world; it was preceded by the prewar campaigning in Weimar Germany around sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, which had campaigned for increased rights for, and study of, sexual and gender-variant people.

Hirschfeld’s scientific approach, combined with his sympathetic treatment of LGBTQ+ people – he was himself homosexual – had been key in developing the idea that their shared experiences could be understood not just as discrete sexual (and criminal) acts, nor as psychiatric illness, but as a legible sexual and gender identity, which could be afforded civil rights. While many of Hirschfeld’s attitudes may seem dated today, they were groundbreaking in providing people with a language to describe and understand their sexual predilections. That research was curtailed, and largely destroyed, by the rise of the Nazis, who ransacked his institute and burned the contents of its archive and library in the streets. When gay people began organising in the US after the war, they were forced to start again from first principles, with only a vague awareness of Hirschfeld’s legacy.

In Los Angeles in 1950, a group of experienced political activists and communists, including Communist party USA member Harry Hay, came together to form the Mattachine Society, one of the first homosexual rights organisations in the US. (Its only predecessor was the Hirschfeld-inspired Society for Human Rights, which was formed in 1924 in Chicago and suppressed by police the following year.) The Mattachine Society had radical roots in activism, taking on the organisational structure of cells and central organisation favoured by the Communist party.

As well as publishing magazines for gay men, and supporting victims of police entrapment, the society had wider political aims, including to “unify homosexuals isolated from their own kind” and to “educate homosexuals and heterosexuals toward an ethical homosexual culture paralleling the cultures of the Negro, Mexican and Jewish peoples”. It wasn’t enough to defend men who had sex with men; rather, a political struggle could only be waged by creating the idea of the homosexual as an identity, in the same political model as other minorities – someone who could recognise him or herself as part of a wider culture. Such aims would become key to the concept of “gay pride” some two decades later.

Those two decades, however, would be among the hardest for LGBTQ+ people in US history, as the greater visibility of the homosexual identity led to a conservative backlash, and a moral panic in the media that was capitalised upon by politicians. In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association included homosexuality in its new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, classifying it as a “sociopathic personality disturbance”. Meanwhile, Senator Joe McCarthy was using public revulsion towards homosexuals in his campaign against leftists. Communists and homosexuals were inextricably linked as anti-American subversives, he argued. Talking to reporters, McCarthy stated: “If you want to be against McCarthy, boys, you’ve got to be either a Communist or a cocksucker.”

In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower passed executive order 10450, prohibiting homosexuals from working for the federal government – an order that stayed in place, in part, until 1995. Ironically, in sacking 5,000 federal employees and thrusting them out of the closet, the red-baiters provided a new cohort of activists for the homophile movement, such as the army map service astronomer Frank Kameny, who devoted the rest of his life to the LGBTQ+ cause. But the so-called “lavender scare” had a cooling effect on the radicalism of groups such as the Mattachine Society and its lesbian sister organisation, the Daughters of Bilitis. After he was forced to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee, Hay was expelled from the Mattachine Society, now a growing organisation of a few thousand men, and he wasn’t the last radical to be thrown out.

The homophile movement began to tackle “subversive elements” and orient itself around respectability. In 1965, following a picket of the White House, Mattachine member Craig Rodwell suggested a yearly protest that would become known as the Annual Reminder. Adhering to a strict dress code of shirt and tie for men and dresses for women, 39 activists from various homophile organisations turned up to “ask for equality, opportunity, dignity”. The bravery of these men and women cannot be overstated, but the approach of quiet, polite lobbying would make few inroads into a culture of institutionalised homophobia. It didn’t matter if homosexuals were successful, law-abiding, and conventional – they were still un-American.

Meanwhile, in cities like New York, a vibrant LGBTQ+ subculture was becoming more visible, despite state suppression. A bar could lose its liquor licence merely for serving a patron it knew to be homosexual, since homosexuals were, by their very nature, regarded as “disorderly”. In 1966, the Mattachine Society challenged this policy with a “sip-in” at Julius’, a Greenwich Village bar that was popular with gay men, but was attempting to shake off its homosexual clientele.

Mafia-run bars frequently flouted this law, exploiting legal loopholes and paying off the NYPD while charging their LGBTQ+ customers high prices for watered-down drinks. Unlike the clientele of Julius’, who tended to be white, middle-class gay men, the Stonewall Inn catered to more ethnically mixed customers, mainly gay men, alongside trans women and some lesbians such as Stormé DeLarverie.

DeLarverie was a woman of colour from New Orleans who performed in male drag as part of the Jewel Box Revue, a black theatre company that toured a drag show with DeLarverie as a besuited compere. She was typical of the clientele of the Stonewall – a fighter, and a survivor of a difficult childhood. DeLarverie was part of the second great migration of black Americans from the south into northern cities, attempting to escape Jim Crow racism and the economic effects of the Great Depression. They brought with them a new influx of culture and ideas that contributed to the explosion of black New York culture known as the Harlem Renaissance, which itself had been kickstarted by the first great migration, which had begun in the 1910s. During the interwar period, performers and authors such as Ma Rainey, Alice Dunbar Nelson and Gladys Bentley had pioneered early lesbian and bisexual cultures as part of a remarkable process of migration, resistance, resettlement and urbanisation, while black male writers such as Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Alain LeRoy Locke also helped to build queer literary and social cultures.

The roots of a Black LGBTQ+ culture – transgressing gender norms, “cross-dressing” and openly discussing their same-sex lovers – were already deeply settled by the time DeLarverie arrived in the city, and it was cultures such as these, as much as the white, middle-class activists who sipped at Julius’, who helped create a meaningful idea of what an LGBTQ+ life might look like.

The creation of the queer cultures that preceded an explicit homosexual political identity was the work of many hands, across many generations. The return and demobilisation of active service personnel following the second world war was part of this story. Men and women who had experienced homosexual sex, relationships and even subcultures in the forces were changed by the experiences, and by war itself. In many cases, they were unwilling to return to their old lives in smalltown America. Port cities like San Francisco and New York in particular became home to many such displaced queers.

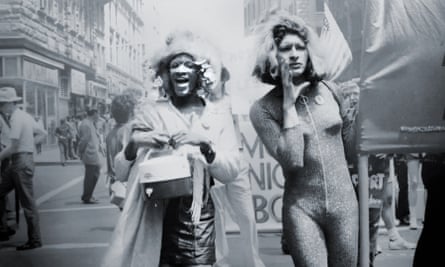

By the time of the riots, there were enough gay bars in New York to necessitate discreet guides for visitors. While gay guides of the time describe bars such as Julius’ and Candy Store as “mixed-collegiate” or “very elegant”, Stonewall was dismissed as a place catering only to young dancers. In the Homosexual Handbook, published in 1969, Angelo D’Arcangelo (sadly a pseudonym) describes it as “a haven of and for narcissists”. Such guides tended to be written by and for more affluent gay men who had enough money to pick and choose. Despite his own reservations about the place, Mattachine activist Dick Leitsch, writing just a month after the riots, acknowledged how Stonewall was more than just a dance bar, catering for those “who are not welcome, or cannot afford, other places of homosexual social gathering”. Stonewall’s regulars were “drags” and “queens”, people who today would likely describe themselves as transgender or gender non-conforming, as well as kids who lived on the street, many underage, who could scrape together the $3 entry, the only door policy at the bar.

Despite the earlier clashes with police in San Francisco, it is Stonewall that is today venerated as a founding myth of the LGBTQ+ movement. It can be hard to tease myth from fact when trying to figure out what happened on the night of 28 June 1969. It was late, people had been drinking and accounts differ. What we do know is that the police performed what they assumed would be a routine raid, and at some point while the queens were being loaded into vans, someone fought back. And it was the queens who were lifted by the cops that night – while the bar was full of cisgender men, they were mostly allowed to move on. Howard Smith, a journalist embedded with the NYPD that night, reported that only “men dressed as women” were arrested in raids, and at Stonewall “three were men and two were changes [trans], even though all said they were girls”.

In his derisive article, Smith recounted how the “turning point came when the police had difficulty keeping a dyke in a patrol car … The crowd shrieked, ‘Police brutality!’ ‘Pigs!’ A few coins sailed through the air.” Most accounts suggest that the “dyke” was DeLarverie, and her cry of “why don’t you guys do something?” caused the place to erupt. Police were trapped inside by the angry crowd, and an attempt was made to burn the place down. By the time riot police had been sent to relieve them, a long suppressed sense of gay rage and frustration had been released. Between 500 and 2,000 rioters gathered in the nearby streets of Greenwich Village, having joined the affray from other gay bars and clubs, and it took nearly another hour to clear the area. By 4am, the riot was over.

The next evening, as a bold provocation to the police, Stonewall reopened. Outside in the street, emboldened by the previous night’s events and subsequent radio coverage, what the Village Voice called “the forces of faggotry” had assembled. The riots continued, on and off, for the rest of the week. There were even calls for the offices of the Village Voice itself to be burned down: people had had enough of being mocked and humiliated.

Stonewall couldn’t have happened without the LGBTQ+ cultures and political groups that preceded it, and they continued to influence the events that followed. But those groups couldn’t contain the rage that permeated the community in the immediate aftermath of the riots, and the months that followed.

The days of the reformist, legal struggles for toleration fought by the Mattachine Society were over. When, concerned by the ongoing unrest, members of the society painted on the boarded-up windows of the Stonewall “WE HOMOSEXUALS PLEAD WITH OUR PEOPLE TO PLEASE HELP MAINTAIN PEACEFUL AND QUIET CONDUCT ON THE STREETS OF THE VILLAGE – MATTACHINE”, their call went unheeded. Yet when the New York chapter called an emergency meeting shortly afterwards, more than 100 LGBTQ+ people showed up. Someone in the audience called for the formation of a “Gay Liberation Front” (GLF), echoing the anticolonial struggles taking place across the Arab world and south-east Asia.

A much more radical fight for sexual liberation and gay power had begun. Many in the homophile movement, such as Martha Shelley, president of the New York chapter of Daughters of Bilitis, helped form, or later joined, the GLF. At that year’s homophile Annual Reminder picket, two lesbians held hands, flouting Mattachine rules. Frank Kameny, the sacked US army astronomer who had since dedicated his life to the cause, was furious, but the women refused to let go of each other. Fellow Mattachine Craig Rodwell denounced Kameny, and over the summer of 1969, the GLF began organising marches and sit-ins, reaching out to other radical groups such as the Black Panther party, and creating a platform based not just on legal rights and tolerance, but around a radical rethinking of gender and families, as well as solidarity with anticolonial struggles.

The GLF was a brief explosion of ideas and political energy. Within months, other organisations had been founded, frustrated by the dominance of cisgender gay men in the group. Star (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) addressed the immediate problems faced by “queens”, trans and gender non-conforming people, many of whom arrived in the city unable to find housing and employment. Another group, Radicalesbians, worked to represent the needs of lesbians who faced misogyny within the GLF, and homophobia within the women’s movement. Meanwhile, the Gay Activists Alliance felt the GLF’s radical social agenda was too broad, and focused solely on addressing gay issues.

The GLF burned out in the US within three years, but that was long enough to establish its most enduring political event: the first Pride march. It was Rodwell who is credited with the idea. As the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations came together for a meeting in November 1969 to discuss the following year’s Annual Reminder, Rodwell wondered whether a commemoration of the riots – one without a dress code or other restrictions, and that could be mirrored across the nation – might not be more suitable. He drafted a resolution, along with his friends, one of whom, Ellen Broidy, presented the resolution, which passed immediately. The first Christopher Street Liberation Day would take place at the end of June. Feminist and bisexual activist Brenda Howard suggested that, rather than just a single march, there should be a week of events surrounding the commemoration. At the same time, GLF activists in other cities, including Chicago, LA and San Francisco, also organised parades. Within a few years there were Pride marches not just across US cities, but in Europe as well, with London holding its first in 1972.

The purpose of Pride was not just to commemorate those who fought back against police violence at the Stonewall Inn, or to protest unjust laws. It was also to counter the sense of shame and self-hatred that scarred the lives of LGBTQ+ people. An early GLF poster featured a photo of a group of young activists, their faces not obscured but visibly smiling, arms locked as they walked down the street, some holding clenched fists in the air. The slogan shouted to other LGBTQ+ people was to “COME OUT!”

To be open about your sexuality or gender identity in your everyday life was a brave political act, but a necessary one. As the Mattachines had claimed, 20 years earlier, if people were to form a political movement, first they needed to find each other, unify and form a shared culture. Now, however, it wasn’t enough to do so discreetly. In sharp contrast with the polite behaviour codes of the earlier homophile protests, a joyous, open celebration of sexuality was a key component of the pride march. “We’ll never have the freedom and civil rights we deserve as human beings unless we stop hiding in closets and in the shelter of anonymity,” one participant told the New York Times. “We have to come out into the open and stop being ashamed, or else people will go on treating us as freaks. This march is an affirmation and declaration of our new pride.”

The two themes that defined Pride from the start – protesting and partying – have long caused tensions within the LGBTQ+ community. Conflicts between gay men and lesbians that were emerging in everyday activism in the early 70s soon found voice during Pride. Many gay activists, while recognising that gender oppression was an intrinsic part of the heterosexual society that targeted them as men, were far from willing to acknowledge their own misogynistic behaviour and attitudes. At the same time, there were tensions around the exclusion of trans people, many of whom described themselves as queens and transvestites, in the language of the LGBTQ+ scene at the time, even while still identifying themselves as gay.

The “gay” umbrella, which brought people together for the cause of liberation, failed to acknowledge the different experiences of those who sheltered under it, or address the power imbalances within it. Sylvia Rivera had first-hand experiences of these problems. As a Latina trans person, rejected by her family and surviving life on the streets through doing sex work, Rivera was attracted to the radical, anticapitalist politics of the GLF, and founded Star to provide shelter and support for trans street kids. Soon, though, she felt the needs of the most excluded were being ignored by the wider gay movement. At the 1973 march, she took to the stage to make their voices heard, despite booing from the crowd:

“Y’all better quiet down. I’ve been trying to get up here all day for your gay brothers and your gay sisters in jail that write me every motherfucking week and ask for your help and you all don’t do a goddamn thing for them … I have been to jail. I have been raped. And beaten. Many times! By men, heterosexual men that do not belong in the homosexual shelter. But do you do anything for me? No. You tell me to go and hide my tail between my legs. I will not put up with this shit. I have been beaten. I have had my nose broken. I have been thrown in jail. I have lost my job. I have lost my apartment for gay liberation and you all treat me this way? What the fuck’s wrong with you all? Think about that! … The people are trying to do something for all of us, and not men and women that belong to a middle-class white club. And that’s what you all belong to!”

Not only was Rivera’s call not heeded by those present who were calling for “liberation”, but as Pride grew, and society became more tolerant, the organisations that arranged Pride marches in the US and Europe began courting brands and companies for the funding needed to host increasingly professional events. During the 80s, worsening public hostility towards homosexuals and trans people meant that sponsorship largely came from gay-owned small businesses, porn stores and nonprofit organisations. But as the purchasing power of the “pink pound” was increasingly recognised, and LGBTQ+ people came to be seen as cool, rather than abject, big corporate sponsors began to move in. At first, they were largely limited to alcohol brands aiming at a young, partying demographic. Absolut Vodka began advertising directly to gay men in the early 80s, and in 1996 New York’s Pride parade secured the backing of beer brand Miller Lite. It wasn’t until the 00s, though, that corporate sponsorship began to overwhelm Pride, as more funding led to larger and larger events, which LGBTQ+ people are now often charged to attend.

In the late 90s, some US activists created Gay Shame in response to Pride’s commercialisation, an event that focused on organising around wider issues that affected the whole LGBTQ+ community. Despite the radical LGBTQ+ organising that took place in response to the Aids crisis – where Pride parades became a locus for awareness-raising protests – many more-radical activists felt that, with increasing corporate involvement, the event was being taken over by liberal activists wanting to assimilate queer lives into becoming a “model minority”, with marriage and military service being a symbol that gay people in particular had “made it”. “If gay marriage is about protecting citizenship, whose citizenship is being protected?” wrote the activist and author Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore in 2005. “Most people in this country – especially those not born rich, white, straight and male – are not full citizens. Gay assimilationists want to make sure they’re on the winning side in the citizenship wars, and see no need to confront the legacies of systemic and systematic US oppression that prevent most people living in this country (and everywhere else) from exercising their supposed ‘rights.’”

Many cities now host “Critical Pride” events that point back to the roots of the march, addressing racism and transphobia within mainstream events, and demanding a return to the countercultural roots of the event, advocating an LGBTQ+ politics that is anti-corporate and against the police and prison system. For many people, the presence of uniformed police at Pride denies them the chance to take part, as police remain perpetrators of racist and transphobic violence. A movement that modelled itself on socialist and anticolonial struggles is, in the US and western Europe, frequently filled with groups representing their employers, including the police and army, arms manufacturers, pharmaceutical giants, oil companies and corporate banks. For those familiar with Pride’s early radical history, at least in intention, today’s parades can sometimes seem bewilderingly depoliticised.

The historical and cultural weight of the main Pride parade, however, still makes it a flashpoint for conflict. In 2018, anti-trans protesters campaigning under the slogan “Get The L Out” disrupted London’s parade, claiming that rights for trans people amounted to “anti-lesbianism” – a claim that would have undoubtedly sounded sadly familiar to participants like Rivera in the first marches almost 50 years ago.

As Pride parades have been organised around the world, LGBTQ+ people have often found themselves as proxies in wider political battles. In recent years accusations have been made that Pride has become part of a “homonationalist” project, where the victories won by LGBTQ+ activists since the 50s, in the face of widespread opposition and hostility, are now portrayed as inevitable products of a national culture. Such a process is used to portray other countries as “less civilised”, despite the role that European empires had in imposing anti-sodomy laws in their colonies and suppressing other cultural approaches to gender. This is doubly ironic, considering the role that US evangelical movements still have in funding political campaigns in many parts of Africa for the continuation or even strengthening of colonial-era anti-sodomy laws. Last year, Richard Grenell, Donald Trump’s ambassador to Germany, attacked Iran, saying that “barbaric public executions are all too common in a country where consensual homosexual relationships are criminalised and punishable by flogging and death”. This is true, of course – but then the same could be said for the US’s close regional ally, Saudi Arabia.

In Russia, both fascists and religious fundamentalists have found attempts to organise Pride marches a potent rallying call, mobilising widespread homophobic feeling by claiming that homosexuality is, in essence, a corrupting import from the west. In 2012, Moscow’s courts banned Pride parades from the city for 100 years. In Poland, nationalist and conservative politicians have found electoral benefit in similar statements; only last year Jarosław Kaczyński, leader of the ruling Law and Justice party, described LGBTQ+ activism as a “foreign imported threat to the nation”.

The use of such rhetoric across the world, and the history of European exportation of homophobic laws, means that attempts by liberal, pro-LGBTQ+ commentators in the west to depict other countries as somehow naturally backwards is often dangerously counterproductive for LGBTQ+ people in those countries. Attempts to build LGBTQ+ cultures and political struggles that emerge from the needs of people within such countries can be written off as creeping Americanisation, or worse, a conscious plot between the US state and LGBTQ+ people to undermine national morality. History, and LGBTQ+ politics, is always more complicated, more queer, than that. Russia, after all, decriminalised all same-sex activity in 1993, a full decade before the US.

Despite emerging in response to the homegrown repression of US society, Pride has now been weaponised by that society – a society still built upon police violence like people experienced at Stonewall – as a sign of how tolerant and open to political change it is. What was once a protest against American values has been co-opted as a defence of those values, even at the expense of the wellbeing and political organising of LGBTQ+ people in other countries, all the while ignoring the fact that LGBTQ+ rights are far from a settled matter at home. In the US, even liberal politicians such as Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama only backed equal rights for LGBTQ+ people within the past decade, and, as Trump’s recent reversal of health protections for transgender people shows, the US continues its long tradition of persecuting LGBTQ+ people.

LGBTQ+ politics is never simple – it’s as much a process of groups of people coming to realise common struggles and common desires, and creating a shared culture, as it is a simple demand for rights. Whether in the US, Europe, Russia or elsewhere, that is a process that can only happen from within, as the history of Pride parades has shown, and not imposed from without.

The impact of the idea of Pride has been so huge that many today assume that the political movements that preceded Stonewall were ineffective, if they know they existed at all. Yet the idea of a gay person or a trans person as an identity that made sense within wider society was not inevitable. It was forged by activists like Harry Hay and Sylvia Rivera, and by the production of an entire culture that acknowledged what people had in common was more meaningful than a mere perversion. By making visibility and “coming out” an organising principle of the movement, they gave millions of regular LGBTQ+ people the confidence and courage to tell friends, families and co-workers that, in the words of the later activist group Queer Nation, they were queer, they were here – get used to it.

The sight of LGBTQ+ people simply enjoying themselves has been as important to that project as any of the more explicit political slogans and strategies – it has made LGBTQ+ people visible to each other. When army specialist Baird read about the Stonewall riots in 1969, he saw himself in them, and his world changed for ever. The purpose of Pride has been to continue that process – to make people visible to themselves, to revolutionise their lives, and to begin to transform social attitudes towards sexuality and gender.

With coronavirus-related restrictions in place this Pride month, hundreds of parades have been cancelled across the world. In response, online versions of the parade are being planned for Pride’s half-century anniversary, including Global Pride 2020. While nothing can mirror the sensation of being a queer person surrounded, at least for a day, by thousands of other queer people, perhaps Pride’s migration online will allow those who can’t attend a physical Pride march, and indeed those who need it most – those taking part hiding in their bedrooms at home, listening on headphones, scared for their door to open – to take part as full, included marchers for the first time. Those of us who have seen our fair share of Pride parades might roll our eyes at its tackier excesses, but for those who still endure the fear and shame of a straight, cisgender society, Pride can be a powerful symbol of a more hopeful life to come.