Egyptian writer and lesbian activist Sarah Hegazi (holding sign) protesting in Canada, where she sought asylum after her arrest, torture, and imprisonment in Cairo.

Credit: Humena for Human Rights and Civic/Public Domain

Battle for LGBTQ rights amid the pandemic

Event takes a global look at how COVID-19 has affected activism, push for solidarity

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted virtually every aspect of life, including social movements such as the struggle for LGBTQ rights. As part of Worldwide Week at Harvard, on Wednesday the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs hosted “Rethinking Resistance Politics in Troubling Times: Transnational Queer Solidarity During COVID-19,” an online panel discussing recent work examining the international situation.

The two-hour-plus forum began with a look at the Arab world. Sa’ed Atshan, visiting assistant professor of anthropology and visiting scholar in Middle Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley, and assistant professor peace and conflict at Swarthmore, opened the Zoom event by discussing the Arab Spring, the series of nonviolent protests launched in Tunisia in 2010. Although these succeeded in toppling dictatorships there and in other nations, the region has in recent years been experiencing a reactionary pushback that has included a rise in officially sanctioned homophobia.

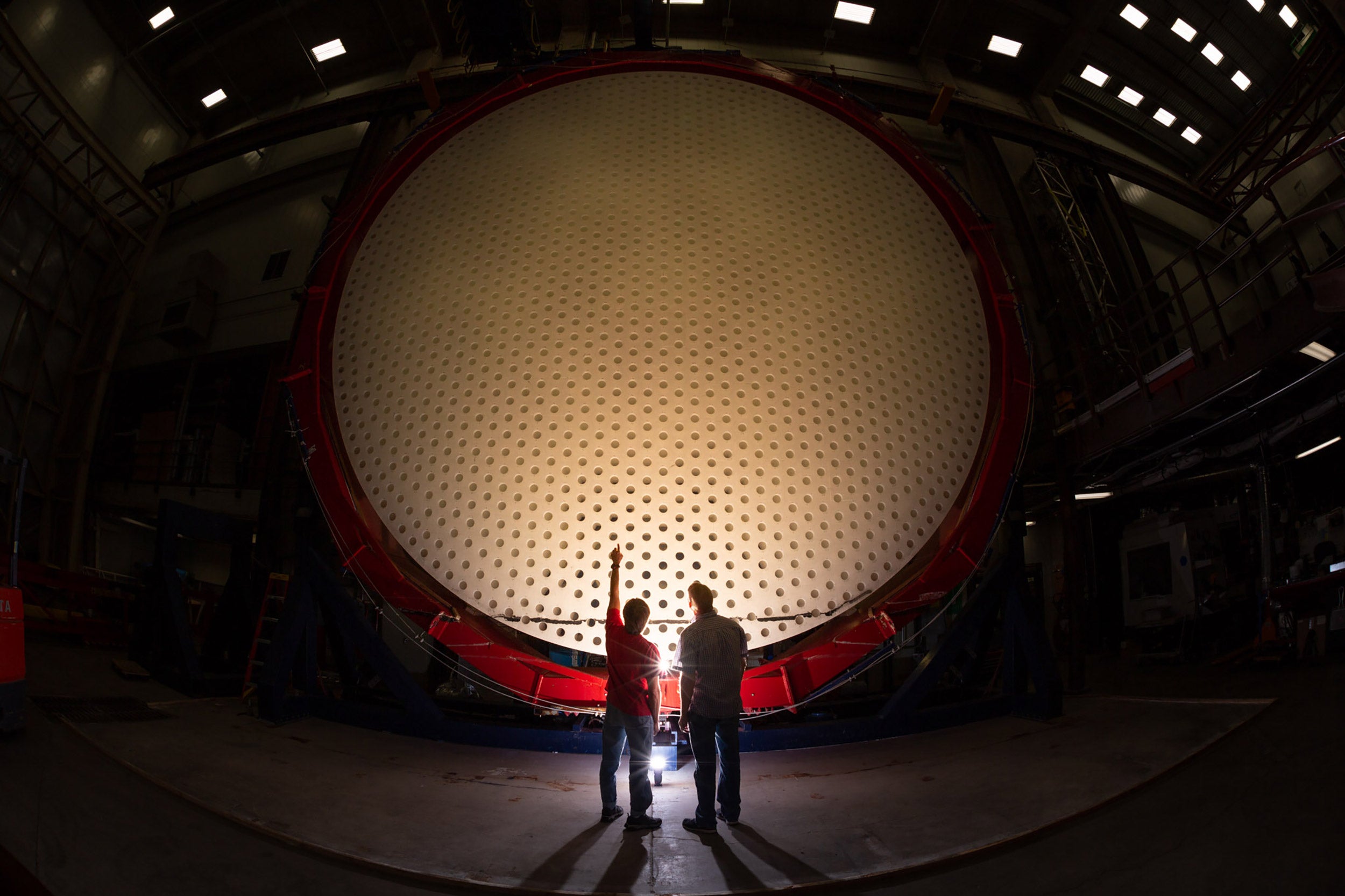

Atshan, who had been a graduate student at the Weatherhead Center, cited as an example the persecution of those who mourned the recent suicide of Sarah Hegazi, who became a cause célèbre for the gay community in the Middle East and beyond. The Egyptian writer and lesbian activist was arrested and tortured by authorities for waving a rainbow flag in 2017 at a concert in Cairo — a city once considered “the queer capital of the Arab world,” said Atshan. She emerged deeply traumatized and depressed and was granted asylum in Canada, where she died in June. This loss, explained Atshan, was exacerbated by the isolation of the pandemic, with widely shared images of Arabs “shaming anyone who mourned her,” he said.

“The deeply entrenched nature of homophobia meant that even in her death she could not rest in peace,” he said. “Queer Arabs had to process this alongside living through a global pandemic.”

Although Beirut appears to be rising as a new center of the queer Arab world, he said, the hard-won gains of 2010 are endangered. “It is clear that the crisis is offering totalitarian regimes cover to consolidate their power,” said Atshan. “The world cannot turn its back on the people of the region, both queer and straight.”

Language offers another frontier in LGBTQ rights, explained the next speaker, Nicole Doerr, associate professor of sociology, and director of the Copenhagen Centre on Political Mobilisation and Social Movement Studies, University of Copenhagen. Delivering her paper “Queer Solidarities in Postmigrant Societies,” she focused on translators, saying, “Social movements today are multilingual movements.”

Doerr’s study of queer migrants and people of color in European movements uncovered both weaknesses and strengths in these increasingly multicultural movements. Looking at Denmark and Sweden, for example, she uncovered that resident migrants, rather than refugees, are the most effective at being heard. “Members of the resident LGBTQ community will not take the refugees seriously,” she said. “You always need some white, middle-class citizen group who wants to work with the multilingual migrant activists.”

However, the translators who work with the migrant and refugee communities — and often come from these communities — have responded. Many are expanding their roles in ways that defy their traditional job definition. “Whites assume translation has to do with language and nothing else,” said Doerr. In the migrant and refugee community, she explained, translation has more to do with ideas and understanding cultural norms.

As translators pushed back against marginalization or racialization, Doerr said, “They develop a counter-hegemonic awareness.” In response, these translators create spaces for new solidarities and dialogue about silenced topics. Translation works by “disrupting dominant culture while remaining in dialogue.”

George Paul Meiu, John and Ruth Hazel Associate Professor of the Social Sciences, Department of Anthropology and Department of African and African American studies, tackled the identification of homosexuality with illness and how that association is playing out amid a global pandemic. Equating homosexuality with illness has deep historical roots. In Africa, in particular, homosexuality is often cast as a Western idea that has “infected” native cultural traditions. The leap to associating it with actual sickness has been made overt by such figures as the president of Burundi, who claimed that “homosexuality is the origin of curses like AIDS and the coronavirus.

During the pandemic especially, homosexuality has been lumped in with globalization as a source of pollution, if not contagion, an idea that supports the fallacy of gay “recruitment.”

In fact, in his study of objects and art that represents “gayness,” Meiu found a surprising similarity of attitudes toward homosexuality and plastics. “Homosexuality or gayism is like a plastic foreign import from the West,” he said, “a form of environmental pollution [that has] nothing to do with African bodies.” Meiu discussed the intentional use of plastics to reclaim the idea of the homosexual body. As the pandemic has restricted mobility, he cited the sharing of queer art over social media as an important entry point for solidarity.

Beginning his talk on “The Great Refusal: The West, the Rest, and the Geopolitics of Homosexuality,” Jason Ferguson, acting assistant professor, department of sociology, University of California, Los Angeles, began by discussing the 2015 arrest of seven men for homosexuality in Senegal — and the international pushback that followed. Both, he said, may be understood as part of larger global trends.

In Western consciousness, Ferguson pointed out, the trend toward liberalization seems clear. Starting in the 1970s, European countries in particular began to move away from homophobic laws toward gender and sexual equality. More recently, however, African and some European countries have begun to swing back toward repression and even criminalization of homosexuality, and the trend toward liberalization has slowed. “By 2015, 40 percent of countries still had to decriminalize homosexuality,” he said. “Gambia increased criminal penalties for homosexuality. Ankara banned LGBT events; even Europe is moving backward on gay rights.”

While these may seem random, such trends may be explained in terms of sociodemographics, he said. That first wave of normalization, for example, coincided with the loosening of the Eastern bloc and Eastern European countries’ desire to join with the more democratic, and wealthier, West. On the other hand, increasing nationalism — particularly among colonized countries — has sparked a pullback from what may be cast as Western decadence or immorality. “The global struggle for gay rights always plays itself out in this theater of inequality,” he said.

Tunay Altay, Ph.D. candidate in social science, Humboldt University of Berlin, focused strictly on Turkey in his paper “In the Grip of Rising Nationalism and the Pandemic: Examining Turkey’s Emerging Digital Queer Spaces.”

Intolerance is increasing in Turkey, said Altay. As an example, he pointed to the canceled production this past July of the original Turkish Netflix series “If Only” because of conflict over a gay character. Although that character was a supporting role and had only nonsexual scenes, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan accused Netflix of “attacking Turkey’s national and spiritual values,” and the series was pulled.

Nevertheless, the country held a digital Pride Month in June, incorporating a slate of online activities that began as early as March and continue today. This has created a divide between the official line and what Altay called “the growing digital visibility of Turkey’s queer communities.”

“Zoom created a safe space” for drag queens, DJs, and others in the community, he said. People learned “we are everywhere.”

The situation remains complex, he pointed out, with a double standard for what is permissible online and in real life. Still, Altay credits the digital world with “giving form to a new regional queer consciousness.”

“It’s a matter of survival,” he said, quoting a Turkish proverb that translates to: “If we ever stop dancing, we shall all turn to stone.”